NormandyTours

This is the second half of our two-part article on the decisions that led Japan to the attack on Pearl Harbor. Last week (Japan’s Road to Pearl Harbor – Part I), we have covered how contact with imperialistic Western powers forced Japan to transform from a feudal state into a modern one; the second part is about the route that took newly-modernized Japan to imperial expansion and conflict with America.

The Meiji Restoration modernized Japan, but needed a guideline for its sweeping reforms, so Japan sent out missions to take stock of the world situation and report back. The most famous of these missions was the Iwakura Mission to the U.S. and Europe in 1871-73. It arrived in Europe at an interesting time: German statesman Otto von Bismarck (the man the famous World War II battleship (Hunting the Bismarck – Part I) (Part II) was named after) had just finished beating the French in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, the final step in unifying the German Empire. This event resonated with the Japanese: like Germany, Japan was also a divided nation that needed unification.

Japan settled on a two-stage plan. First, westernize domestic institutions; second, start an empire in Asia. It’s important to understand that imperialistic expansion was not merely a matter of greed; Japan genuinely believed it was a matter of national life and death. For one, if Japan was to be accepted by the Western powers as an equal rather than a target for subjugation, it had to act like they did, and they all had their own overseas empires. Secondly, Japan was lacking in many natural resources including oil and iron, and while trading for vital commodities was a possible solution, extracting them for the nation’s own colonies promised more security.

With Japan westernizing and modernizing, the Western powers no longer had an excuse for the unequal treaties and the treaty port system. Britain was the first to repeal its former arrangements. Satisfied that British citizens would no longer fall victim to capricious or cruel non-Western Japanese laws, Britain signed the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Commerce and Navigation on July 16, 1894 (though it only came into effect five years later), effectively repealing the previous unfair arrangements. Other countries soon followed with revisions of their own treaties with Japan.

Japan startled flexing its military muscle later in the month, and its target was the former, now ailing giant of Asia: China. The flashpoint of the conflict was Korea. Korea had traditionally been subordinate to China, but China was under Western domination and could do little to control or protect its charge. Korea was violently divided into two factions: one wanted to strengthen the traditional ties with China, while the other wanted to follow Japan’s example and modernize. Japan supported this latter faction, since their aid in modernizing Korea would have guaranteed them influence in the country. That influence, in turn, would give them access to Korea’s significant natural resources. Another consideration behind the involvement in Korea was that of security: as long as Korea was unstable and China weak, another power (most likely Imperial Russia) could have established a foothold there and used it as a springboard for aggression against Japan.

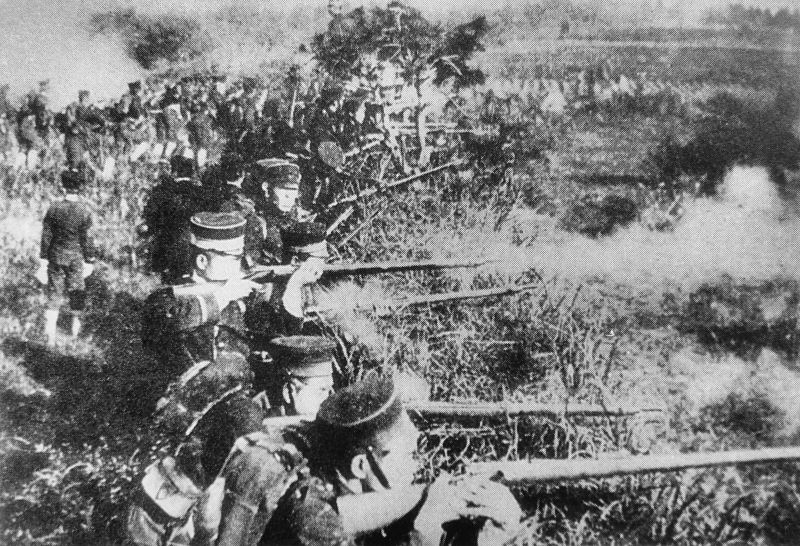

The 1st Sino-Japanese War started in 1894. The government called in Chinese troops for help with a peasant rebellion. Japan claimed that the Chinese presence in Korea violated an earlier agreement (it technically did, as China did not inform Japan of the intervention beforehand), and used it as an excuse to send its own intervention force. Neither side was willing to back down, and Japan’s new, modern military dealt China a devastating defeat, not only pushing them out of Korea but also entering Manchuria.

The Treaty of Shimonoseki shook up the Asian status quo. China, the continent’s great old civilization, was humiliated and forced to pay Japan 17.6 million pounds (8 metric tons) of silver as indemnity. Japan began building its sphere of influence by conquering Taiwan and the Pescadores Islands. The formerly controversial westernization and modernization program proved its value. The Western powers acknowledged Japan as a Great Power.

On the downside for Japan, it could not keep the Liaodong Peninsula with the major port of Port Arthur, a territory it captured in the war. An intervention and military threat by Russia, Germany and France persuaded Japan to leave this area… which was then quickly occupied by Russia, while other Western nations took other bites out of freshly weakened China. Japan felt cheated out of its rightful spoils and was determined to prevent future cases of multiple Western powers allying against it. This direction led to increased spending on heavy industry and the navy at the cost of individual comforts for the populace. Diplomatically, Japan sought a European ally and found it in Britian, which signed the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1902.

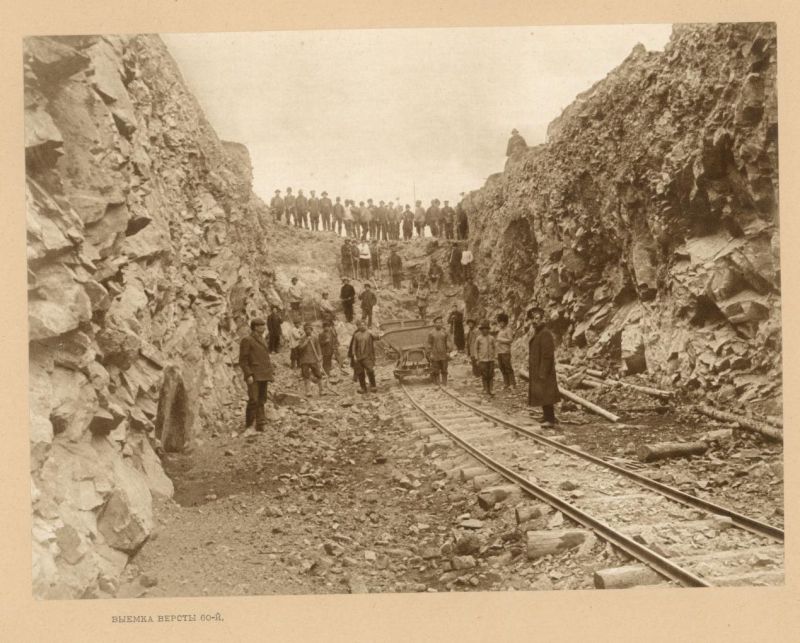

Japan’s rapid rise was not lost on Russia, which had been eyeing the Far East since the 16th century. Russia far exceeded Japan in manpower, but faced one major disadvantage in its bid for power in China: distance. China was close to Japan, but very far from the highly populated western parts of Russia with no way of getting troops to the Far East. Russia began constructing the famous Trans-Siberian Railway in 1891 specifically to enable the mass transport of troops and supplies to the Far East. Japan knew it had a limited time window to seize Manchuria, the northeastern part of China rich in resources. Once Russia finished the railroad, any Japanese army there would be buried by superior Russian numbers.

Japan’s first step was to isolate Russia from its potential allies. The already mentioned Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902 achieved this. It stated that if more than one European power came to Asia to fight Japan, Britain would enter the war on Japan’s side. This meant that Russia would have to fight alone, since no country would be willing to help it and thus get on the wrong side of the British Empire in a war. (As far as Britain was concerned, hobbling Russia like this also meant it wouldn’t be a threat to India, the crown jewel of Britain’s own empire.)

Russia continued to expand into the Far East, nevertheless. Port Arthur, which Japan didn’t get to keep after the war, became a Russian naval base, and was going to be eventually connected to the Trans-Siberian Railway. Russia was also making inroads in Korea. Tsar Nicholas II was dismissive of Japanese protests about this intrusion into their sphere of influence; he was guided by his personal racism (he called the Japanese “yellow monkeys”) and by Russia’s own imperial arrogance; he was also being egged on by his cousin, Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany, whose “Yellow Peril” propaganda fed into Nicholas’s own prejudices. (For his part, Wilhelm figured that if Russia concentrated on Asia, it would pay less attention to tensions between Russia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which was Germany’s ally.)

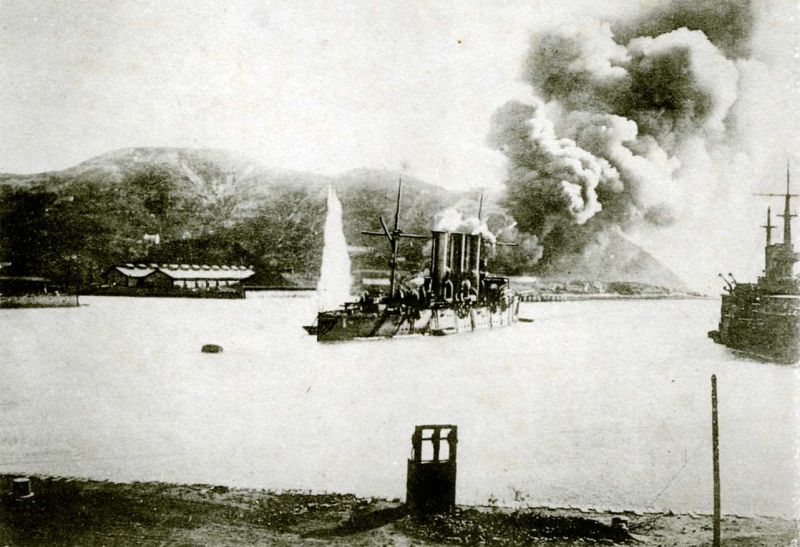

Tensions turned into open conflict in February 1904, when the Japanese Navy attacked Port Arthur. The Russo-Japanese War lasted a year and a half and was tough going for both sides. Japan had spent the silver it got from China as reparations on the military build-up before the war, and had to fight on loans. The Japanese Army struggled with taking Port Arthur and supplying troops inland; they were so short on artillery that naval guns had to be taken off of warships and put into service on land. On the other hand, the Russians suffered serious losses in several battles, including the humiliating naval Battle of Tsushima: Japan sunk 7 Russian battleships and 14 other vessels, and captured 4 battleships and a destroyer, at the cost of losing 3 torpedo boats

On land, Russian troops looted and burned Chinese villages, raped women and murdered civilians who resisted or simply didn’t understand Russian orders. Meanwhile, the Japanese genuinely worked to improve sanitation and the road network. (This was obviously not all altruistic; the improvements also protected their troops from disease and improved strategic mobility.)

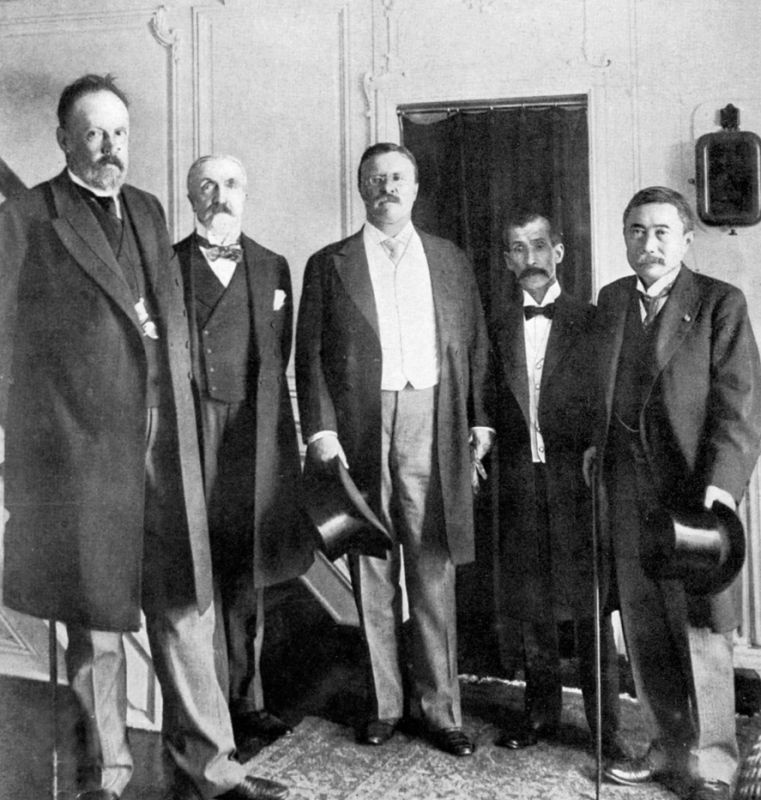

Nevertheless, Russian numerical superiority was getting worse and worse, and Japanese supply lines were one defeat away from collapsing. Fortunately for the Japanese, they had already planned an exit strategy. A Japanese personal acquaintance of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt asked him to mediate a piece between Japan and Russia, a request Roosevelt enthusiastically agreed to after reading up on bushido, the samurai spirit.

The Treaty of Portsmouth, engineered by Roosevelt, ended the war and got him the Nobel Peace Prize. Russia accepted Japan’s influence in Korea (and Japan later annexed the country, using it as the gateway for later expansion on the Asian mainland). Japan got to keep the island of Sakhalin, a formerly Russian territory, and Port Arthur. On the other hand, Russia did not pay reparations or concede the Russian Far East. With more Russian troops arriving into the theater of war, the Japanese delegation decided not to press the issue. The Japanese public, however, wanted territorial gains and reparations as compensation for all the lives lost, and felt cheated by the peace treaty, their resentment towards most European powers now expanded to include America, which negotiated the “unfair” treaty.

Internationally, Japan became the undisputed dominant power in Asia. Domestically, the balance of power shifted away from civilian politicians and towards the military; the people felt that “the diplomats lost the peace, but the generals won the war.”

Emperor Meiji died in 1912 and was succeeded by Emperor Taishō. His rule, as well as the years before and after, are known as the Taishō Democracy, when Japan made strides towards a modern democratic state. Mandatory schooling introduced in the Meiji era created a literate populace and a call for greater popular participation in politics. Industrialization created an urban working class and a labor movement. Party politics, universal male suffrage and a vibrant social discourse held bright promises for the future. Japan signed several international treaties to preserve the status quo and peace in the Pacific.

When World War I broke out, Japan contacted Britain with an offer: it would help the Entente side by capturing German island colonies in the Pacific if it could then keep those islands. These islands expanded Japan’s empire and formed the network of strongholds that Japan later used in World War II. Japan also sent warships and important supplies to Europe to help the war effort there.

Emperor Taishō died in 1926 and his period of relative democracy soon crumbled. A massive 1923 earthquake, a banking crisis and the effects of the Great Depression caused unemployment and poverty. The resulting social unrest encouraged voices in the military to call for a strong hand, a foreign policy that supported Japan’s needs and an end to divisive party politics.

It should be noted that American treatment of the Great Depression also contributed to Japan’s radicalization. The Smoot-Hawkey Tariff Act of 1930 placed steep tariffs in a wide range of imports with unforeseen consequences. The goal of the act was to encourage domestic production. American importers had to pay tariffs on foreign goods. Therefore, it became cheaper to buy similar goods from domestic producers, encouraging the creation of jobs.

The problem was that if America discourages imports from other countries while other countries allow their own traders to buy things from America cheaply, then more money will flow into America from elsewhere than the other way around, which will take money out of the national economies of those other countries. Therefore, other countries must also introduce tariffs to encourage their own domestic economies. And once every country produces everything domestically and no international trade is happening due to high tariffs all around, the biggest losers will be countries that don’t have natural resources to produce goods with – like Japan. From Japan’s perspective, there was one way out: conquering territories which have the raw materials, like steel or rubber, that the country needs.

The period of peace ended in September 1931, when the Kwantung Army, stationed in the part of Manchuria taken from Russia, invaded the rest of Manchuria. This was done on their own initiative, against orders by Imperial General Headquarters, presenting them with a fait accompli. This was in the spirit of gekokujō (“the low overcomes the high”), a practice that dated back to the divided Japan of the feudal era. Gekokujō could simply meaning overthrowing one’s superior, or it could mean, as it often did in the 1930s, doing something that “had to be done” “for the greater good” without or even despite orders. Once the invasion started, it took Japan 5 months to conquer Manchuria. The region’s natural resources became a lifeline for Japan, poor in resources itself and cut off from international trade by high tariffs.

The realization that the military could do anything they wanted without proper oversight threw the civilian government into disarray. The early years of the reign of Hirohito, the recently crowned Emperor Shōwa, saw a drift to right-wing authoritarianism. The U.S. closed off Japanese immigration to the states, sinking relationships between the two countries. In naval treaties, Britain and the U.S. tried to limit the size of the Japanese Navy as smaller than their own. The military was split into two political factions with different ideas about Japan’s future, but they agreed that civilians have no business running the country. Japan became ruled by “government by assassination,” with military cabals doing away with anyone in their way. Japan’s recently acquired national identity and the obsession with bushido made the populace receptive to ideas of military rule and conquest.

Firmly in control of the nation, the military began the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 to conquer the rest of China. This war was a far cry from the first one, with Japan combining rapid strikes and superior technology with terror bombing, biological and chemical weapons and the “Three Alls policy”: Kill All, Burn All, Loot All.

Japan expanded its operations and also invaded French Indochina after France fell to Nazi Germany in Europe. The U.S. demanded that Japan withdraw from China and the formerly French territories, and introduced trade embargoes on oil, scrap iron and munitions, commodities Japan needed to continue the war.

Having just lost 94% of its oil import, Japan decided its only course of action was to take some by force. Burma and the Dutch East Indies were both oil producers, but it was clear the U.S. would not stand by and watch Japan invade the colonies of its allies. A fateful decision was made: surprise and incapacitate the U.S. Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor, rendering America unable to prevent the invasion of oil fields. The mistake in the plan was misunderstanding American psychology and how the nation would react to the attack. Based on their own culture and their experience in modern warfare, Japan assumed that the U.S., once bloodied, would quickly accept a peace and let Japan prosecute its war against other. What really happened was that Japan (to cite a quote often, likely incorrectly, attributed to Admiral Yamamoto (Yamamoto – Part I) (Part II)), “awakened a sleeping giant and filled him with a terrible resolve.”

If you would like to learn more about the currents of history that led to the attack on Pearl Harbor, the details of the “day of infamy,” and America’s entry into World War II, join us on our Pearl Harbor Anniversary Tour!