NormandyTours

Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor (and a simultaneous invasion of many locations across the Pacific) was one of the most momentous events of World War II. It shocked the American nation, silenced the isolationists and ensured the country’s entry into the war on the Allied side. America’s entry, in turn, doomed Japan to eventual failure. Japan’s most famous admiral, Isoroku Yamamoto (Yamamoto – Part I) (Part II), expressed doubt about how a war against the U.S. would go after the first few years. Considering the vast disparity between America and Japan in industrial production, the result of the war seems like a foregone conclusion, at least with the benefit of hindsight.

So why did Japan start such a war? The reasons behind the attack are usually glossed over with a pithy but vague “conflict of imperial ambitions,” which is less than satisfactory for such an important even. This article will give you a rundown of the deeper history behind Japan’s decision, starting with their country getting unwillingly dragged onto the world stage in the 19th century and examining how certain political and economic factors put the country in a corner where its leadership felt it had no alternative to war.

In the early 17th century, a daimyo (Japanese feudal lord) called Tokugawa Ieyasu unified Japan by force, ending a 150-year period of civil wars and social upheaval. He became shōgun, a military ruler of Japan. Shoguns are ostensibly appointed by the emperor, but Tokugawa (like several other shoguns before him) was practically the true ruler of the country, while the Emperor was reduced to a revered but powerless figurehead. The Tokugawa shogunate reigned from 1603 to 1868, and was one of the more peaceful periods of Japanese history.

One of Tokugawa’s major policies, which his successors also adhered to, was the isolation of Japan from the rest of the world to prevent other countries from meddling with Japan’s fragile internal stability. International trade was largely shut down, foreigners were forbidden to enter the country, and Japanese were not allowed to go abroad. Isolation was not complete, though; diplomatic relations and a significant amount of trade was still maintained with China, which was the political and cultural center of Southeast Asia; and to a far lesser degree with Korea. Contact with the Western world was reduced to a single small Dutch trading post maintained on an artificial island off Nagasaki, which allowed limited goods, as well as knowledge of Western science, technology and medicine, to trickle into Japan.

Another major Tokugawa measure was the division of Japanese society into rigid classes to avoid social mobility, which was considered to be a threat to stability. Below the Imperial family, the courts and the shogun was the warrior nobility, the samurai class; below them the peasants who produced all the food; then the artisans; and then the lowly merchants who created nothing. At the bottom were the burakumin, the untouchable outcasts who included butchers, tanners, executioners and undertakers.

The Tokugawa shogunate operated well enough for over two hundred years. Interestingly, much of the bushido, the samurai code, was formalized in this period, when samurai didn’t actually really fight any wars. The tenets of bushido, including the ideas that honorable death is preferable to defeat and that determination and willpower can and should compensate for a lack of resources would later inform Japanese military attitudes and decisions during World War II.

The social order constructed by Tokugawa started creaking under the strain in the mid-19th century. Many merchant families managed to accumulate great wealth during the long peace, but social rigidity prevented them from turning wealth into political power. Farmers who had fallen on hard times had to sell their land to wealthier farmers, becoming tenants on their own former properties, while the landowners were blocked from social advancement. Lower ranking samurai in bureaucratic positions were frustrated by their inability to advance into more powerful positions.

Samurai were paid their fixed stipends in rice, which was vulnerable to market fluctuations; there was also less and less rice to go around, as other crops became more profitable for farmers to grow and sell. The development of urban lifestyle also meant that samurai had to pay for more things to maintain a respectable lifestyle, and many of them were in constant debt.

The Japanese way of life was also under threat from abroad. The Russian Empire started looking eastwards for expansion in the early 19th century. A Russian nobleman raided Japanese settlements in Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands in 1804 after Japan refused to trade with the Tsar.

The Napoleonic Wars broke out in Europe in 1803, and the United Kingdom assumed control of Dutch colonies in Southeast Asia after Napoleon conquered the Netherlands. The Dutch trading station in Japan was supplied by neutral ships, but the British started paying more attention to events in the region.

Even more threateningly to Japan, the First Opium War began in China in 1839. Three years later, it ended with the humiliation of Southeast Asia’s cultural touchstone as Britain forced the country to open its ports to trade, more specifically the trade of British-produced opium. This began China’s “century of humiliation”: the country was forced to trade with European traders whether it wanted to or not, the Europeans got to decide the customs duties paid on various goods (and could therefore control what was traded and in what quantities), and Europeans living near the “treaty ports” where the trade was conducted enjoyed “extraterritorial privileges,” meaning they were not subject to Chinese laws. It was quite clear to Japan that they too could become the victims of such treatment by Western powers. Information about the war was suppressed in Japan, but the daimyos still learned about it and were on the edge.

And then came the event known in Japan as “the arrival of the Black Ships.” The black ships in question were a U.S. fleet commanded by Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry. Perry’s mission was to open up Japan to trade with the U.S. America’s main interest in Japan was as a supply base: American ships conducting trade with China and American whalers in the Pacific needed a place where they could acquire supplies, including coal for fuel.

Perry made two expeditions to Japan between 1852 and 1855 in a display of typical gunboat diplomacy: ignoring Japanese demands to depart, humiliating officials by refusing to meet them in person, firing blank shots and making explicit threats. The council of elders advising the shogun were shocked and paralyzed with indecision. In the end, Japan gave in, designated two cities as treaty ports and, along with a follow-up second treaty, gave American seamen and representatives the same privileges Westerners also enjoyed in China.

Tasting blood in the water, Britain, Russia and France quickly forced Japan to sign similar treaties with them between 1854 and 1858. Japan was on the way to being subjugated by Western powers for good.

The reaction to the so-called “unequal treaties” was extreme, even from political faction that had previously advocated compromise and a gradual opening of the country, but which were dismayed by the extent of humiliating concessions. A new political movement adopted an old slogan: sonnō jōi – “revere the Emperor, expel the barbarians.” The first half of the slogan was leveled against the shogunate, which was seen as having failed to protect Japanese interests, and therefore had no business ruling in the Emperor’s stead. The second half was a call for an obvious solution. It should be noted that several major clans supporting the movement had no compunction about buying weapons, ships and other technology from the West.

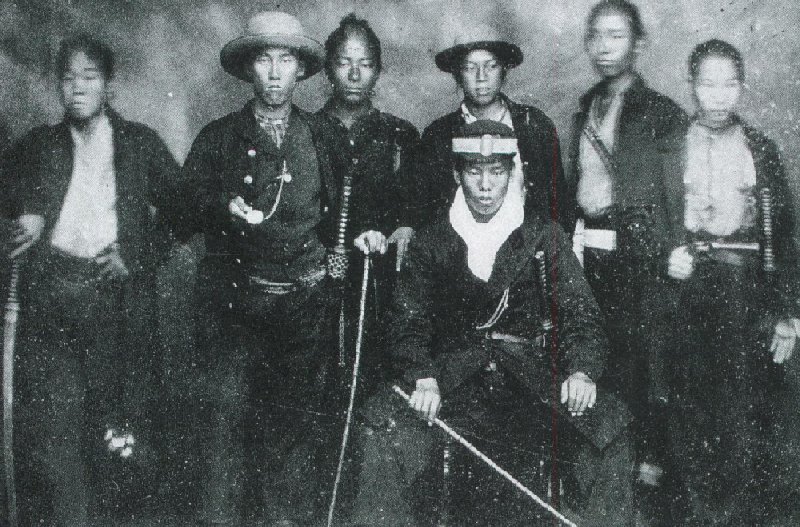

Emperor Kōmei personally agreed with the movement, and broke centuries of tradition by starting to take an active role in politics. In 1863, he issued the “order to expel barbarians.” Of course, the Emperor did not have any practical power, and the shogun had no intention of enforcing the order. Nevertheless, the Emperor’s support encouraged the Japanese to make a stronger stand. A new group of political activists called shishi (“men of spirit”, mainly lower and middle-ranking samurai) started acting in the spirit of the order. Some encouraged education as a weapon against Western oppression, while others resorted to assassinations.

The Westerners fought back to preserve their privileges. Chōshū Domain defied the shogunate by opening fire on Western ships passing through a strait in the summer of 1863. In response, a coalition of Western nations launched a punitive military campaign which ended with the beheading of the rebel leaders and the Westerners forcing the shogunate to open a new treaty port. In the same summer, the murder of a British citizen resulted in a British bombardment of Kagoshima. In the end, the murderers were never identified or arrested, but the local Satsuma Domain agreed to pay indemnity. (Ironically, this act of conciliation formed the seed of a British-Japanese cooperation that became very useful to Japan later on.) These events further proved that the shogunate was too weak to protect Japan against Western exploitation, and encouraged clans already aligned against the shogun.

Tensions got to the point of armed uprisings, two of which the shogunate managed to suppress. The third, an alliance by the Chōshū and Satsuma Domains, turned out to be the one the shogunate choked on. Chōshū forces well-organized and equipped with modern weapons bought from Britain, while the shogun’s army largely comprised antiquated feudal units. Additionally, several clans neighboring Chōshū refused to join the shogunate and decided to wait out the conflict. As a result, a 4,000-strong Chōshū force defeated a shogunate army numbering 100-150,000 with only 261 deaths in June 1866.

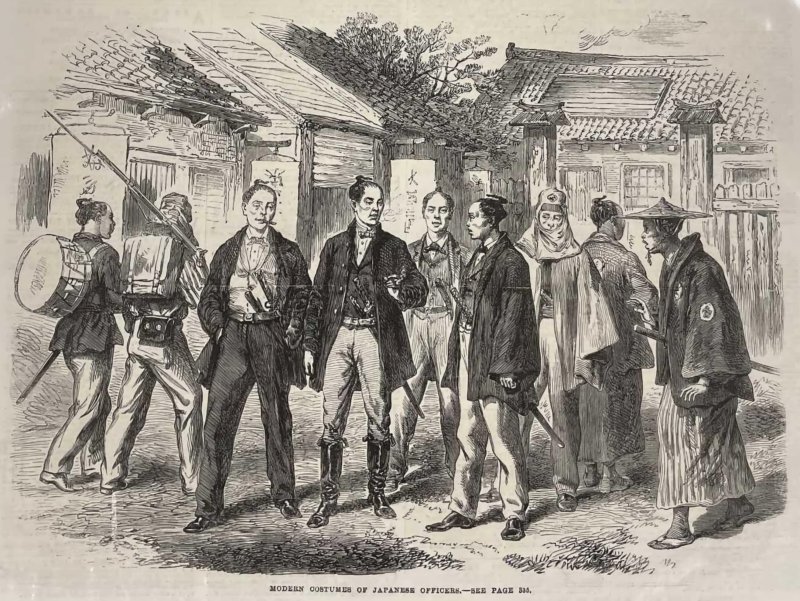

The shogunate was humiliated, and Shogun Tokugawa Iemochi died two months later. His successor negotiated a ceasefire, but the shogunate’s prestige was in tatters. The new shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, tried to salvage the unsalvageable by introducing reforms to modernize the administration and the military, and by inviting a French military mission into the country. Emperor Kōmei also died the next year and was succeeded by his teenage son Mutsuhito as Emperor Meiji. He was young, ambitious and willing to restore the Imperial throne to real power.

The shogunate was in a precarious position. Rebellious domains were preparing for war, and the officials of loyalist domains were busy jockeying for positions in the inevitable new order. The shogun tried to maintain his title and influence by renouncing the administrative functions of the shogun in late 1867 and returning those to the Imperial Court. On January 3 the next year, troops from anti-shogunate clans seized the Imperial palace. With their support, Emperor Meiji proclaimed an end to the shogunate.

Tokugawa Yoshinobu was no longer shogun, but he was still free and at the head of his clan. The Chōshū and Satsuma domain wanted him gone for good, while the Tokugawa clan took up arms in self-defense. The resulting conflict was the Boshin War, also known as the Japanese Civil War, and it established a new order in Japan. Lasting a year and a half, the war involved relatively limited bloodshed and ended with Emperor Meiji the undisputed ruler of Japan and Yoshinobu retiring from politics. As a note of American interest, the first ironclad warship of the Imperial Japanese Navy, the Kōtetsu, which fought in the Boshin War, formerly served the Confederacy in the American Civil War as the CSS Stonewall.

Sitting firmly on the Imperial throne, Meiji set about reforming Japan into a state that could stand up to the Western powers and whose reigns were in his hands, rather than in those of disparate feudal lords. He abolished the feudal han system that divided the country into domains, and replaced them with prefectures answering to the central government. He offered titles, stipends and offices to daimyo who willingly went along with this curtailment of their power.

Meiji also abolished the samurai class and replaced their rice stipends with government bonds. Many former samurai ended up in the state bureaucracy, which gave them a similar level of prestige as what they enjoyed previously. Others ended up as teachers, gun makers or officers in the new national army. Importantly, this new army was built through national conscription and answered directly to the emperor without any civilian oversight by the government; this feature became a major cause for Japan’s slide into military dictatorship before World War II.

The Meiji Restoration turned Japan into the first Asian state to modernize according to the Western model. Free mandatory schooling was introduced for children, and a standardized national version of the language was adopted. Rapid industrialization and the proliferation of private enterprise turned Japan into an economic powerhouse. The country’s chief export commodity was raw silk, the production of which even outstripped China’s. The slogan of “Revere the Emperor, expel the barbarians” was replaced with fukoku kyōhei, “Enrich the Country, Strengthen the Armed Forces.”

The transformation into a modern nation was not without its detractors. The leader of Satsuma Domain, one of the former key supporters of the emperor, felt the reforms were going in the wrong direction with the abolition of the samurai and the inclusion of the common people in the political process, and staged a rebellion which he died in in 1877.

The unequal treaties with Western powers that caused so much resentment were still in place, but not for much longer. Japan had stepped onto the world stage, looked around, and decided that if it was to survive, it needed to become a proper empire.

Our article will continue with the events that sent Japan on the path of imperial expansion and eventual war with the West.